For a minute there, I thought I was going to a private screening. When I bought my ticket for the 3:00 pm showing of Melania only forty minutes before showtime, every seat in the house was available. By the time I got to the theater, a couple was sat behind me. A few minutes later, a man walked in and pronounced to the room, “So it’s the four of us who are doing this thing, huh?”

By the time the movie started, there were nine people in Theater 2 of the Alamo Drafthouse, about a third of the relatively small room’s capacity. This was a frigid Saturday afternoon in New York City, where Brett Ratner’s documentary has been advertised relentlessly. That $40 million budget is running away fast.

Not that the box office for Melania was ever the point. Jeff Bezos spent a rounding error on Melania’s vanity project because he wanted $40 million worth of access and goodwill. This film isn’t a loss, it’s an in-kind donation. Brett Ratner directed it because he hasn’t worked since 2014, and when you’re credibly accused of rape and sexual assault by multiple women, you have to take the opportunities that present themselves. This is a film made by and about bad people. It is a particularly heinous artifact of the age in which we are living.

Given that, I can understand why the man who came into the theater after me felt the need to preemptively absolve himself, to assure everyone that he was only here to watch the train wreck. Attending Melania invites suspicion in an area that’s heavily blue-coded. You have to actively choose not to wonder about your fellow attendees, to wonder what they think about you. I myself spent the first half of the movie trying to work out whether the older immigrant sitting to my right was there with the same distancing irony as many of us seemed to be, or if she was there for a genuine experience.

I was there because I wanted to know how Mrs. I Don’t Care Do U? would present herself to the world when she has all of the creative control. What would and wouldn’t she show us? How does Melania, who is remarkably absent from the public eye given her position, want us to see her? This intrigued me. Also, frankly, I’d been home sick all week, I had nothing else to do, and a Melania screening seemed the least likely place in New York City to run into other people outside of my apartment.

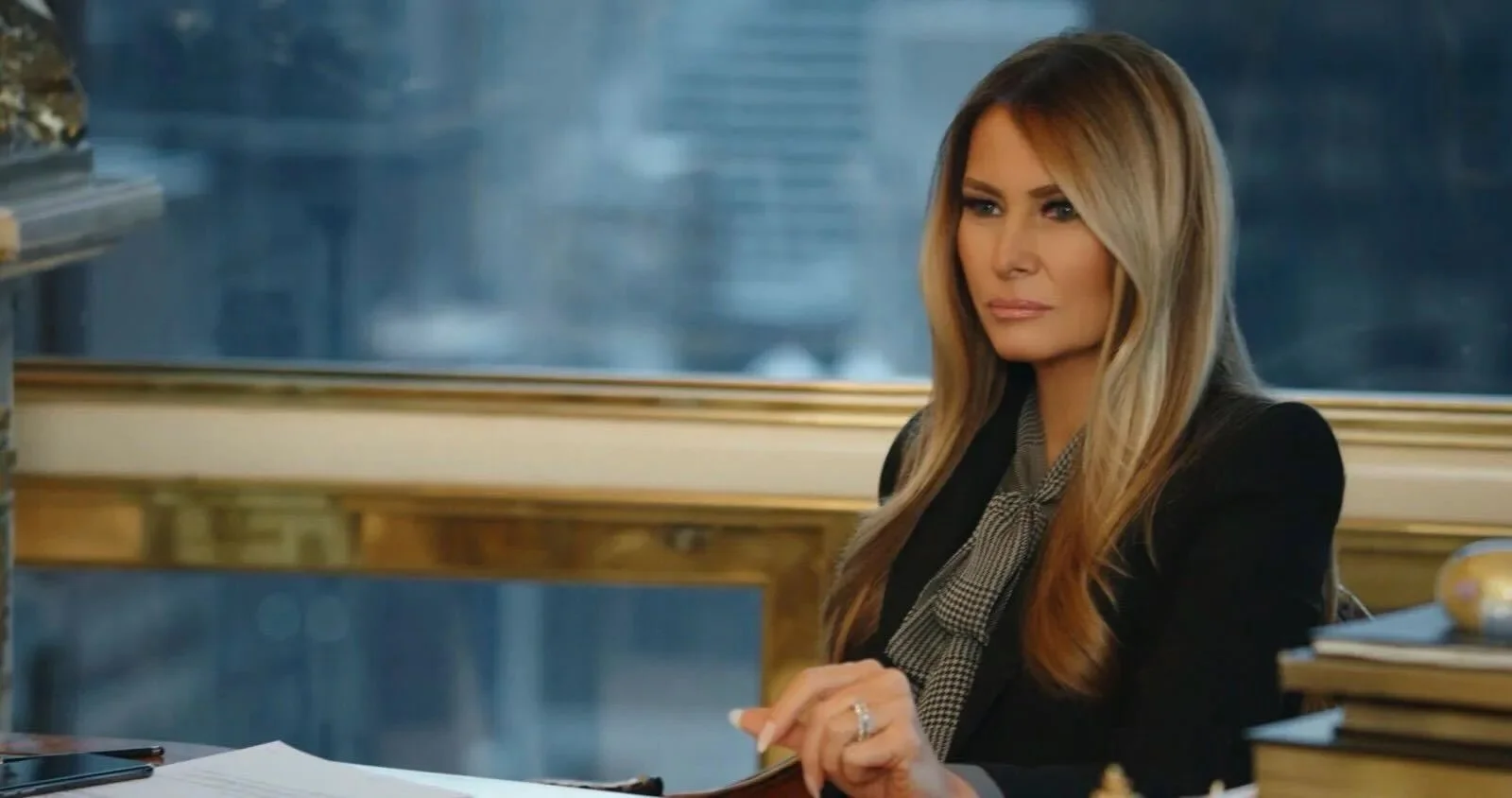

For 104 minutes, I watched Melania walk, drive, and fly around the United States in preparation for her husband’s second inauguration. I watched her sit at tables and have vacuous conversations with global figures. I listened to her recite a voiceover consisting mostly of pleasantries and pablum. As a narrative experience, Melania is remarkably, achingly dull. It isn’t even good in a pro forma sense. More than once, I thought, “My kingdom for a Riefenstahl.” If you’re going to script out and plan your documentary in advance, as much of this seems to be, at least make it so impacting that I find myself getting carried away with it, that I can gaze at the screen with horror rather than with the vague disdain of the unimpressed.

Fortunately, Melania is fascinating as an object. Like most propaganda, it is more valuable for what it doesn’t show us. The cameras followed Melania for twenty days, and this is what they got. During that time, we never once see her talk to a friend. She never chats with her dad or her son, Baron. We don’t see her engage in any hobbies, or pursue any interests. The only social call she has with her husband, even, is on the night of the election, and it turns out he talks to her more or less the same way he talks to an arena full of his supporters. “Did you watch [the results come in]?” “No, but I’ll see it on the news.” First of all, it’s astonishing that she didn’t watch the results come in. Just. You know. Really consider that. It wasn’t out of nerves, but utter disinterest. Wild stuff. “Oh, you should watch it. It’s incredible. They’ve never seen anything like it. We won every swing state,” etc., etc. By the end of this 30-second phone call, she is already visibly bored and eager to get off the phone. Donald seems happy to keep talking, bless.

If you were to mention this lack of a social or personal life, this staggering lack of interiority, the filmmakers would likely claim that she was simply too busy, but if there’s one thing Melania makes abundantly clear despite itself, it’s that this lady has a lot of idle time. She’s constantly on the move, yes, but she is on the move in chauffeured cars and private planes. Her life is full of opportunities to read, to call a friend, to text with people, and a documentary that’s interested in humanizing its subject, as this one is, would absolutely include those moments if they had happened. The likelier explanation is that they didn’t.

In many ways, I think Melania is about convincing its subject that hers is a full and worthwhile life. This documentary is a performance of First Ladydom from a First Lady who does significantly less than her predecessors. She has a meeting with Brigitte Trogneux, her French counterpart, to talk about a cyberbullying initiative, and is carefully shown dutifully taking a single note on a notepad roughly the right size for a grocery list. You know, like serious and important people do when discussing international policy. She has a private meeting with the Queen of Jordan during which none of their advisors are present. She talks about being responsible for running the East Wing of the White House, which, well, let’s just say that that’s been a part-time job since October of last year. Her desk is always immaculate and empty, the surest sign that she’s not in charge of anything.

Most striking, she constantly reiterates that the designs for the inauguration were all her doing, but we see the actual designer showing her the designs he prepared. We see him adjusting the tables and squaring up the placards. We see his assistants scrub down all the mirrors in his office for the initial presentation. Melania expresses preferences about her inauguration outfit, but it is the (immigrant) designer and the (immigrant) tailors who affect the requested changes (It is worth noting that Melania is at her most animated and engaged when talking about her dress for the inauguration, though her sense of style is so severe that it looks out of place amongst the living.). She’s rubber stamping things, yes, but that’s not the same as doing the work. It’s as though she has been out of touch with running her own life, with pulling the levers of daily decisions and practicalities, for so long that she doesn’t even know how to fake it anymore.

If the question is, “How does Melania want us to see her,” then I’m afraid the answer isn’t particularly interesting. She wants us to see her as competent, busy, dedicated, dutiful, loving. Based on the evidence, I think very little of that is true. This is a cynical and manipulative ploy, an attempt to take advantage of the relatively blank canvas that is her public persona and paint it with rosy colors.

How cynical is up for debate, but I keep coming back to a moment just before Trump’s inauguration speech, when he’s doing the final run-through of the draft. Melania, who outside of this documentary regularly shows herself to be beyond disinterested in the life and work of her husband, sits dutifully in the room, watching him run the speech, and suggests an addition that everyone in the room receives warmly. “Don’t film this, but she had a great idea,” Trump jokes to the camera. During the actual inauguration, after delivering that line, he takes an enormous pause to turn back and smile at her while giving her a thumbs up. I would buy that sort of thing from the Obamas, but Jack and Rose the Trumps are not. Several hours after getting home from the movie, it occurred to me that all of that was all almost certainly scripted for the benefit of the documentary.

For all the incompetence evident here, for how transparent the exercise is, it works for the faithful. The older immigrant to my right, a Peruvian woman who’d brought her adult daughter with her, was indeed there for a genuine experience, and she loved the movie. She pumped her fist when Trump spoke, and footage of Melania’s father filming on a Super8 camera evoked a quiet, “That’s so sweet.” We ended up in a conversation with two other attendees, a writer covering the movie and her friend.

“Why did you come to the movie,” the writer asked her. “Do you like Trump?”

“You know, I never liked him, but then I saw how mean everyone was being to him, and I decided they weren’t being fair. They want him to be presidential, but he isn’t, you know? He’s genuine. He is who he is. And I like her.”

Melania doesn’t grapple with the political, the existential, or even the practical in any direct sense. It offers plenty to chew on around the edges, though it offers these things blithely and unintentionally. Just about every person who speaks on camera in the first 45 minutes of the movie is an immigrant. Footage of her lighting a candle for her late mother in St. Patrick’s Cathedral is underscored by Aretha Franklin’s version of “Amazing Grace,” a decision whose racial politics could fuel an entire dissertation. She talks briefly about her experience as an (illegal) immigrant. Late in the film, her narration offers us, “Everyone should do what they can to protect our individual rights. We cannot take them for granted. Because in the end we share our humanity.”

After the movie, I asked the Peruvian woman about that. “What do you think about what she said in the movie about immigration and rights giving everything that’s going on at the moment?”

“When I came here, I told myself, you have to learn the language, you have to learn to read and write, and I made myself legal. And I think people have a right to come here, but they don’t have a right to push their ways on this place. They have to adapt. I voted for him three times, you know?”

I got the impression she’d be pretty happy to do it again. I didn’t get the chance to ask.

Melania ends with her official White House portrait photo session. We first see painted portraits of Eleanor Roosevelt, Mamie Eisenhower, and Jacqueline Kennedy. I kept waiting for Ratner to cut back to more portraits, he never did. Those choices were intentional. Roosevelt and Kennedy are, of course, the two most canonically beloved First Ladies. It would be in poor taste to leave them off any First Lady’s list of personal heroes. But Mamie was interesting, and the exclusion of any First Lady more recent than the mid-60s was telling. Here at last, Melania presents an intentional and competent statement, about the type of First Lady Melania wants you to think of her as, and the type of First Lady the Trump Administration wants you to idolize.

In retrospect, Melania could only end with the portrait session. This movie is all about the image.